Welcome to Heartland Masala HQ! My name is Auyon Mukharji, and this is where I’ll be publishing a semimonthly newsletter about Heartland Masala, a cookbook that my mother Jyoti and I will be releasing in September of 2025.

For this inaugural post, I’d like to celebrate two writers who influenced the shape of the book. The first is José R. Ralat, who holds the enviable position of Taco Editor at Texas Monthly Magazine, and who also wrote a book called American Tacos: A History and Guide (University of Texas Press, 2020).

American Tacos is not a cookbook, nor does it contain any recipes. It is instead closer to a field guide, illustrating the enormous breadth and rich history of tacos—breakfast, puffy, barbecue, K-Mex, Indo-Mex, etc.—across the country. I love the author’s framing of the evolution of the taco as both natural and legitimate. In response to the ever-dominant lens of cultural ownership within food writing today, it feels almost revolutionary.

A guiding light in Ralat’s writing is what he refers to as the Abuelita Principle, which he describes as follows:

Mexican Americans have been known to pump their fists in the air with cries of inauthenticity upon encountering a cheesy taco like the alambres. This El Paso favorite tops grilled beef, soft bacon, and bell pepper with a lacy cap of Muenster cheese. “My abuelita made real Mexican food! That is not Mexican food,” they insist. Everyone’s abuelita—Spanish for “little grandmother” and Anglo code for “authentic Mexican cook”—prepared real Mexican food. It’s true. It isn’t true. Authenticity only exists on paper. Every family tweaks recipes according to their tastes, creating a new, distinct Mexican food that changes with the street address. This is the Abuelita Principle. It simultaneously informs and undermines the dynamic culinary culture that is Mexican food.

The problem is that the Abuelita Principle can dampen the full enjoyment of a gastronomy that is kinetic and expansive. It restricts Mexican food to a nonexistent rigid ideal. Lebanese immigrants—or Iraqi immigrants, depending on whom you ask—are behind the creation of tacos al pastor. Pork isn’t indigenous to the New World. Yet, tacos al pastor are seen as an iconic Mexican dish.

The Abuelita Principle is ignorance at its best, racism at its worst. Let the food go. Revel in its vibrancy. Let it play. When you’re ready, take a bite without making a knee-jerk criticism. You might be surprised. And American tacos, in particular, have much to offer in the way of surprises. (11)

Ralat’s criticism resonated deeply with me. To treat a single relative as the sole arbiter of authenticity (a frequent occurrence in cookbooks of family recipes) is to both neglect the broader historical context of a given dish and deny the inevitable expansion and transfiguration of culture and cooking at large.

Another writer who describes a related phenomenon within the Indian food space is the anonymous author of My Annoying Opinions, a food and whisky blog with sporadic (and excellent) food writing criticism. In the provocatively titled Against Family: Covering the Coverage of Indian Food (2019), the anonymous author describes how the current focus on family within Indian food writing has produced a series of “narratives [revolving] around upper class, upper caste westernized Hindu families.” The author makes clear that they are not universally against family-focused writing, but they do worry that it “threatens to become effectively the only one in which Indian food culture is talked about in the US, and it severely limits the discourse.”

This worry concerned me too, especially since the core of our book Heartland Masala is around 100 of my mom’s favorite recipes, culled from the many hundreds she has taught through her cooking classes. Since many of these dishes are family recipes, Heartland Masala is at least in one sense part of the very problem outlined by the author: yet another collection of (mostly) family recipes from an upper-middle class immigrant family. A conundrum!

In charting a path forward, I found direction both in Ralat’s detailed taco histories and in the counsel of TW Lim (“What if you really lean into the nerdiness?”), which plunged me into a years-long Indian culinary history deep dive. Since family orientation is baked into our book’s premise, my hope was that by presenting slices of broader cultural context alongside the dishes, we’d be able to avoid, or at least temper, both the false promise of single-household authenticity (vis-à-vis the Abuelita Principle) and the insularity of family-dominated food writing.

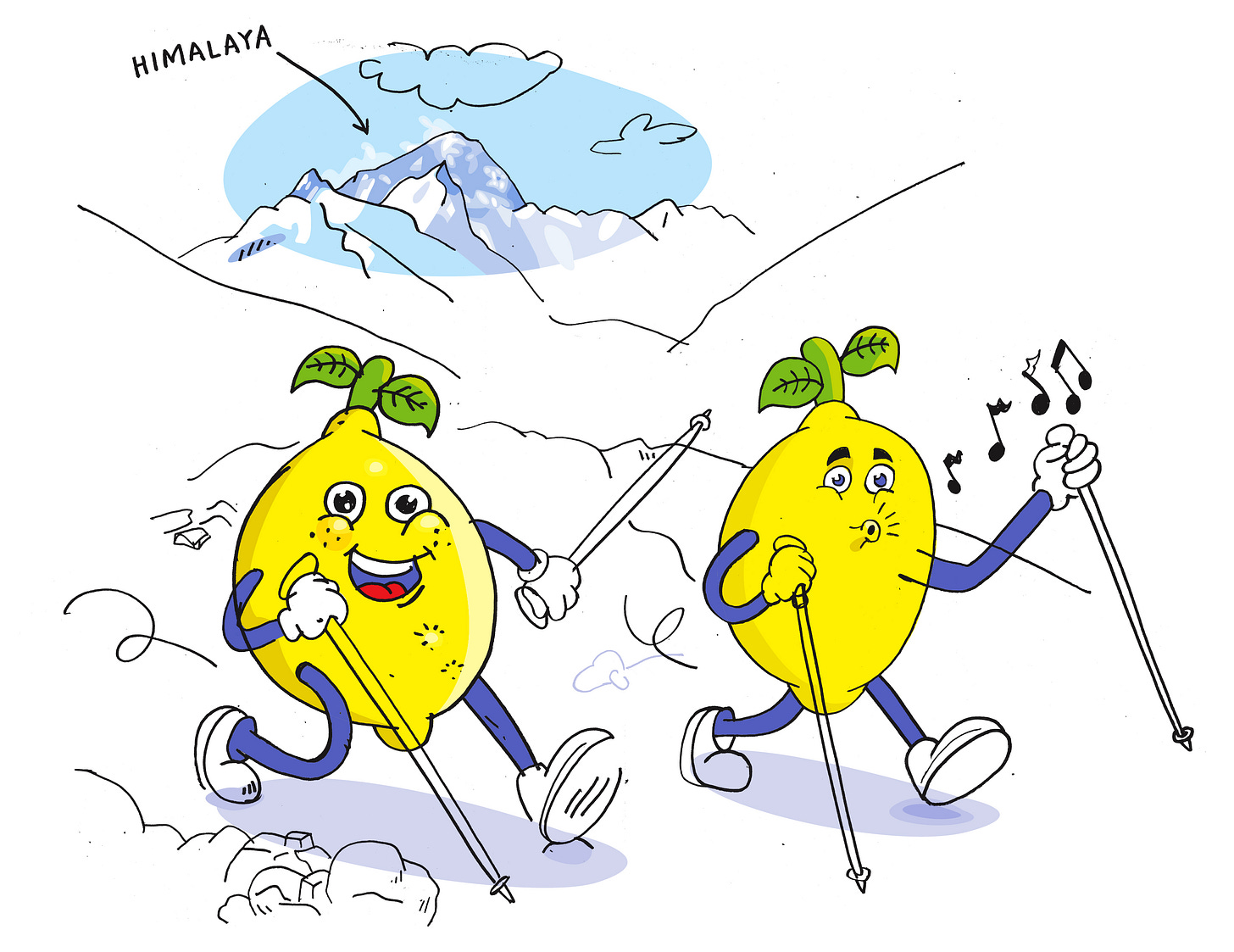

The result is an atypical cookbook, which isn’t necessarily a good thing marketing-wise, but it is our thing and we’re proud of it. My mom and I are both illustrated characters, and most of our headnotes (pre-recipe blurbs) are split between the two of us. Her headnotes deal with her Indian upbringing and teaching experience, while mine are mostly concerned with history, context, and etymology. Interspersed throughout the recipes are roughly 20 illustrated mini-essays, including a piece on the evolution of chai, a warning about daal bubble monsters erupting out of your cooking vessel, and a brief history of lemonade ingredients in India.

That’s all for this installment. I’ll leave you with my favorite illustration from the book, which accompanies our lemonade vignette When the Himalaya Give You Lemons.*

Until soon,

Auyon

© 2025 Olivier Kugler // Heartland Masala

*In Sanskrit, the term Himalaya (“abode of snow”) is the same in both its singular and plural forms, so we’ve chosen to follow suit etymologically and drop the s. Both versions of the name (Himalaya and the more common Himalayas) are acceptable ways to refer to the mountain range in English.

I just learned so many things! And had fun doing it. Can't wait for more.

Well done! Looking forward to your next post.